Tigray is sadly best known in the developed world for its famines and as the war-torn front in the conflict between Ethiopia and Eritrea. What it should be known for, however, is its 120 rock-hewn churches; some dating back to the 5th century, hidden away on mountain-tops and built into caves on high cliff faces.

Until the 1960s these churches were largely unknown outside Ethiopia. Unlike those in Lalibela which are concentrated in one village, these are scattered across the region and are often inaccessible. Few tourists make it to these churches; many will not have been visited for decades. However, like those in Lalibela, many are still active sites of worship and in fact I saw a new one being built into the side of a mountain during my journey there.

Many of the churches have painted murals and ceilings with scenes from the New Testament or the story of St. George and the dragon. They contain great church treasures and jewelled crucifixes that have sadly in recent years been suffering the attention of bounty hunters.

I hiked over to the church of Abuna Yemata in the Gheralta region which involved climbing 50 metres up a vertical cliff and then negotiating a narrow ledge above a 250 metre drop. There, quite relaxed and almost as if he had been waiting for my arrival was a handsome young priest in his Sunday best looking as if he had just stepped out of a Vogue shoot.

The church of Daniel Korkor was a further three-hour hike under a midday sun. Like Abuna Yemata it was built into a mountain top cave and has views reminiscent of Monument Valley in the USA. The elderly monk meditated, gazing out from his cliff edge eyrie, close to the heavens and far from the troubles of the material world below.

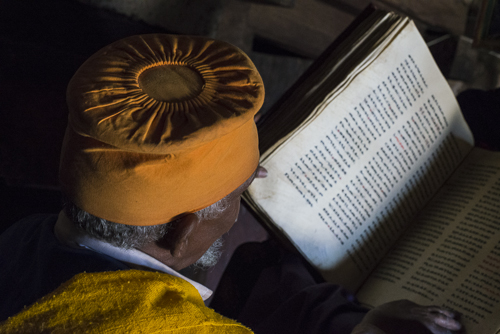

Debre Damo is a 6th century monastery that sits 3000m high on flat-topped mountain near the town of Adigrat. Famous for its impregnability, it’s also home to the oldest existing church in Ethiopia and a fantastic collection of ancient illustrated manuscripts.

As ever, the story of its origins lies embedded in myth. One explanation is that Abuna Aregawi, its founder, was carried to the top on the wings of a flying serpent. When I visited this men-only monastery I had no such transport at my disposal and was hauled on a leather rope 300 metres up a cliff by a monk with very mischievous eyes. On my way back down he asked for a tip – if ever there was a man I was going to tip, this was he.

The monastery supposedly hosts over a 100 monks but they must have been in hiding as I only came across a couple, one of whom was keen to show me a magnificent bible written in the old religious language of Ge’ez on cured goatskin.

In trekking across Tigray I came across spectacular views and hidden cave churches that no one had a name for. I could have spent months exploring this land and not seen a fraction of its secrets. Here I met very few tourists and the people in this very poor part of the country were the most gracious and generous I came across. Both the priests in their mountaintop lairs and the laity doing their best to farm this arid land were most welcoming. I stumbled across several weddings, each one insisting I share in the festivities and consume their Tej, a local and potent mead.

However, times are changing and the Chinese are bulldozing several highways across Tigray, over the land and through the villages. Perhaps the tourist coaches will soon follow and the elderly priest at Daniel Korkor will look down at them trailing dust in their inexplicable hurry.